The economy was in freefall. Unemployment was skyrocketing. And Congress was coming to the rescue.

The COVID-19 crisis in 2020? No, the financial bailout of 2008, when the country was experiencing what is now known as the Great Recession.

Today’s pandemic-driven economic meltdown is different from the financial shocks of 2008. But some of the lessons journalists learned in covering them are similar. In sessions for National Press Foundation fellows, two veteran reporters detailed how they covered financial crises of old, and how journalists today can track the unprecedented trillions that Congress and the Federal Reserve have deployed to keep the economy from sinking further.

James B. Steele, part of the legendary Barlett and Steele double byline that won two Pulitzer Prizes, two National Magazine Awards and six George Polk Awards, detailed his reporting approach to “Good Billions After Bad,” an investigation of the slapdash approach the government took with its Troubled Asset Relief Program in 2008. (Background on the program from a 2020 Congressional Budget Office report.)

Kathleen Day, a Johns Hopkins University business professor and previously a Washington Post reporter, talked about the history of financial crises she detailed in her book “Broken Bargain.”

The TARP program Steele wrote about was hugely controversial at the time, in part because of the way the U.S. Treasury Department essentially force-fed banks the money, hoping to spur lending as the housing market collapsed and the economy cratered.

What Steele and reporting partner Donald L. Barlett found is that the Treasury department had no idea where the money went after it left government hands, or whether it in fact aided the recovery. Did it save the banks from collapse? The “Treasury Department had no idea, and didn’t seem to care,” they wrote in Vanity Fair.

“The Treasury Department decided the way to help the problem was to throw money at it,” Steele told fellows.

The duo’s story started with Freedom of Information Act requests that unearthed, in one example, a one-page, four-line agreement that sent $25 billion in taxpayer money to J.P. Morgan Chase & Co.

Their story – like the bulk of Barlett and Steele’s work over their career – was built on case studies, such as that of a bank that didn’t want the money but was strong-armed by Treasury officials into taking it.

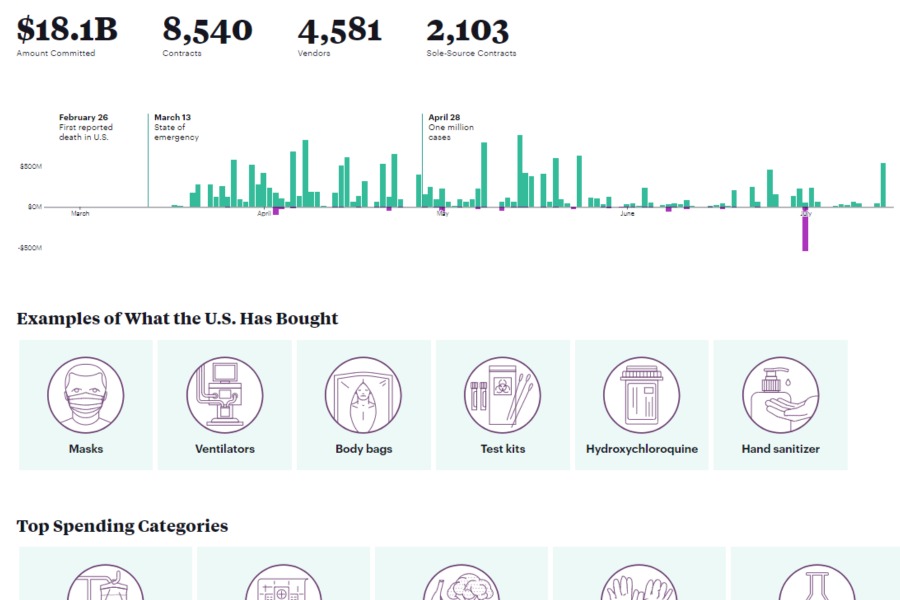

While Steele’s bailout story was focused on the 2008 TARP program, his lessons could apply to the COVID stimulus as well. As in 2008, Congress is shoveling money out the door as quickly as possible. The rules are ever-changing and the oversight scant. And money is being spread widely – to businesses, nonprofits, hospitals, schools, churches and other institutions across the country.

Steele’s advice to reporters:

- Reread documents — especially the boring ones. You won’t absorb the dull details the first time. But once you know more and reread, you may spot oddities.

- Never assume anything—starting with how to spell someone’s name.

- Talk to inspectors general in federal agencies, or their staff. Their job is to spot abuses.

Day’s book focuses on the banking sector, which has repeatedly been bailed out by taxpayers. Those bailouts generally came after banks and borrowers got hooked on easy credit.

Day offered tips for digging into local businesses, particularly financial services companies:

- Talk to local businesses who got the money – or didn’t. Local businesses want to talk. And competitors love to rat on competitors.

- Go to state regulators. Their documentation isn’t as rigorous as federal records, but they can spot anomalies. If they won’t talk, go to former state regulators.

- Get to know the regional Federal Reserve Banks. They will know which institutions come more often than they used to get a loan.

- Look at the corporate debt load of any corporations based in your reporting areas. It could have national implications.

When looking at Securities and Exchange Commission documents, the best things are proxy statements (known as form “DEF 14A.”) These are often more telling than the annual reports corporations file with the SEC because lawyers are required to disclose anything that could be a risk to the company.

This program is funded by the Evelyn Y. Davis Foundation. NPF is solely responsible for the content.